Last Updated on January 3, 2022 by Heather Hart, ACSM EP, CSCS

As a running coach, there are a number of “running confessions” I hear routinely from new clients. One of the most common ones is something along the lines of “I know I should probably strength train…but I don’t.”

While I personally love lifting and my time spent in the weight room, hearing this confession never surprises me. Over the last decade as both an Exercise Physiologist and runner myself, I’ve made the following observations about my fellow runners, when it comes to strength training:

- If runners are limited on training time, they would rather run than strength train (this isn’t inherently a bad thing, more on this soon).

- Runners simply don’t enjoy strength training, and would rather run.

- Runners are unsure if strength training is even necessary, since they are already so active.

- Runners fear strength training might make them bulky or “tight”, and thus slow them down or negatively affect running performance.

- Runners want to strength train, but are unsure of where to begin or how to fit it in with their run training.

There are a lot of misconceptions and misunderstandings when it comes to weight lifting and running. In this post, we’ll discuss the various pros and cons of strength training for trail and ultra runners, so you can determine if combining weight lifting with your run training is right for you.

Strength Training for Trail & Ultra Runners: the Basics

Before we really dive into the potential benefits of strength training for trail and ultra runners, as well as the potential drawbacks, let’s first cover the basics of strength training, how it works, and what it does for your body.

What is Strength Training?

You probably already know this one. But just to be thorough, let’s define it. Strength training – also referred to as resistance training, weight training, or “lifting weights” – is any exercise that causes the muscles to contract against an external resistance. That source of resistance can be just about anything, from a cast iron barbell, to an elastic resistance band, to the resistance caused by moving your very own body weight against gravity.

Not all sources or loads of resistance, nor repetition volume or frequency will yield the same results. The very simple rule of thumb is that lifting a heavy weight (relative to YOUR strength) over a low number of repetitions typically results in muscle hypertrophy (increasing muscle mass), and activates Type 2 muscle fibers (“fast twitch”), which have greater power but fatigue quickly.

On the other hand, lifting lighter weights (again, relative to your strength) over a higher number of reps will increase muscular endurance (the ability for your muscle to continuously contract against a given resistance or movement) and will help develop Type 1 muscle fibers (“slow twitch”) that are endurance based and slow to fatigue.

What Happens When We Strength Train:

Let’s get a little more specific: strength training places a demand on the neuromuscular system, which promotes motor unit recruitment, muscle fiber firing frequency, and greater demands of intramuscular coordination (5) As a result of strength training, over time muscle fibers are activated earlier, in greater number, and more efficiently.

This improved coordination between muscle units produces:

- Muscles that can better facilitate the absorption of ground reaction forces.

- A faster rate and capacity for force development – or how effectively you can push against the ground/road/trail when running.

In short, this capacity to generate higher forces may reduce the energy needed to actually run. More on this below:

Potential Benefits of Strength Training for Trail & Ultrarunners

The topic of strength training and running in general – not just ultrarunning – has certainly come with polarizing opinions. I will likely say this a dozen times throughout this post, but it’s important to remember that specificity of training matters. When it comes to training for an ultramarathon, running is the priority. No other form of training is an adequate substitute for running.

However, there are a number of reasons why ultrarunners may want implement strength training around their run training if they can do so in a way that does not hinder their running. These possible reasons include:

Possible Improvements in Running Economy:

Running economy is a measure of how much oxygen (or energy) your body requires to run at a particular pace. Remember above, when we talked about how strength training may increase a runner’s ability to generate higher forces, and thus may reduce the energy needed to actually run?

A systematic review and meta-analysis looked at 5 separate research studies, involving a total of 93 high-level middle- and long-distance runners, to determine if strength training programs had an effect on running economy. The meta-analysis demonstrated there was an overall, significant, large beneficial effect of the strength training interventions on running economy (upwards of 2-4%) when compared with the control group (3).

In short: the study found that a strength training program including low to high intensity resistance exercises as well as explosive and plyometric training performed 2-3 times per week for 8-12 weeks is an effective way to improve running economy in highly trained middle- and long-distance runners.

However, it’s important to remember that research also shows an improvement in running economy when run training volume (total running distance) increases. So while strength training is definitely advantageous, it should be noted that running workouts are certainly more specific when it comes to training for trail and ultrarunning goals.

Delaying Onset of Fatigue While Running:

This one is pretty straight forward: strength training improves neuromuscular capacity to produce force and power, which can improve running economy (see above), which can delay the onset muscle fatigue.

In short: if it takes less energy for you to run at a given effort, the longer/further you will be able to run before experiencing fatigue.

Possible Injury Prevention / Reduction:

It has been routinely touted among the running world that strength training can help prevent running injuries. But how?

Overuse Injury Prevention:

Overuse injuries, or chronic injuries, are injuries caused by repetitive movements (like, you guessed it, running). Unfortunately, these are wildly common: studies show that upwards of 70% of runners sustain an overuse running injury each year (6)

Maintaining Muscle Mass:

Whether we like it or not, muscle loss is a part of life. Age-related muscle loss, called sarcopenia, is a natural part of aging. After age 30, you begin to lose as much as 3% to 5% per decade. (7)

Decreases in muscle mass (and the accompanying decrease in muscle strength) not only results in a loss of functional ability, but also increases the risk for musculoskeletal injury. Strength training programs may then reduce the risk for musculoskeletal injuries related to muscle imbalance (10)

Bone Density & Strength

Much like muscle, bone tissue has the ability to remodel and adapt to the physical stresses imposed on it. Numerous studies have demonstrated that strength training can cause increased bone mineral content and therefore may aid in prevention of skeletal injuries.

Ligament & Tendon Strength

According to a 2016 review of the role of strength training in preventing musculoskeletal injuries, studies have shown that strength training can lead to increases in both the size and strength of tendons (connective tissue that connects muscle to bone) and ligaments (connective tissue that connects bone to bone).

Further, research has demonstrated that increases in muscle mass are likely met by increases in the size and strength of the connective tissue, leading to an increased tensile strength (10) More muscle mass = stronger ligaments & tendons.

Acute Injury Prevention:

An acute injury is a an injury that happens suddenly and unexpectedly, such as a sprained ankle from landing on a tree root, etc. According to a meta-analysis performed by Dr Jeppe Bo Lauersen in 2018, it is believed that strength training can help prevent acute injuries by facilitating:

- improved coordination

- enhanced technique

- strengthening of adjacent tissues reducing critical joint loads

- better psychological perception of high-risk situations. (2)

In other words, strength training can make you better at either avoiding a potential fall/twist/etc. in the first place, and/or reacting quickly enough to a misstep (etc.) in a way to prevent injury.

Overall Health Benefits:

We DO know that regular strength/resistance training is beneficial for overall health. According to The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) , the benefits of resistance training include:

Improved physical performance, movement control, walking speed, functional independence, cognitive abilities, and self-esteem (11).

Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes by improving insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance.

May enhance cardiovascular health through improving body composition and decreasing risks of metabolic conditions.

Bone Density: we lose bone density at the rate of 1% per year after age 40. As bones grow more fragile and susceptible to fracture, they are more likely to fracture or break. Weight bearing exercises can not only help slow the rate of bone loss, they encourage bone growth, increasing density.

It’s important to remember, running is only weight bearing on the lower body, and does nothing to help slow the rate of bone loss in the upper body.

Building upper body strength through resistance training will help maintain a healthy, strong bone density in the upper body, a benefit that is not obtained from simply running .

Pain Relief: May be effective for reducing low back pain and easing discomfort associated with arthritis and fibromyalgia

Reverse muscle aging: Strength training as been shown to reverse specific aging factors in skeletal muscle (11)

ACSM currently recommends that a strength training program should be performed a minimum of two non-consecutive days each week, with one set of 8 to 12 repetitions for healthy adults or 10 to 15 repetitions for older and frail individuals.

Anecdotal Evidence

Endless trail and ultrarunners will give you their own experiences as to why they believe strength training is vital for their training and racing. From believing it helps prevent injuries, to simply “feeling” stronger during the endless miles, or on long climbs or descents, or over the tough and sometimes demanding terrain of trails, runners will tell you that they believe it works.

Personally, I agree. I definitely feel that I am a much stronger, well rounded athlete since I’ve been incorporating regular strength training into my running routine. An example: I often hear ultrarunners complain about sore shoulders from carrying a hydration pack for hours and hours on end. Me? I never experience that, and would like to think it’s because I spend 4-5 days a week in the gym working on my upper body strength.

You Simply Enjoy Strength Training:

Those who have been following me or reading my work for a while now know one training approach I will always, always respect: and that is that YOUR running journey is YOURS. We only have one life to live, and sometimes, finding joy in life means that perhaps you make sacrifices in certain areas in order to truly live.

For me, my strength training approach may not be perfectly complimentary to my ultrarunning, but that’s because I enjoy both. I want to do both. And while I try to balance both in a way that they are complimentary, personally I believe that the health benefits I receive from strength training outweigh any potential negatives to my ultramarathon training or performance.

Potential Drawbacks of Strength Training for Trail & Ultra Runners

All of the glowing recommendations for strength training aside, there certainly are potential drawbacks to combining weight lifting with your trail or ultramarathon race training.

Detracts from the Specificity of Training

In the exercise science world, we have a number of training principles that, when properly understood and applied, can help guide an athlete to training and performance success. The Principle of Specificity states that sport performance improves through training movement patterns and intensities of a specific task and fitness type. Incorporating specific tasks of a sport will induce neuromuscular and metabolic adaptations to improve specific structure, fitness, and exercise economy of the overloaded muscle groups (8)

In other words: in order to get better at a sport specific skill, you must perform THAT skill.

In order to get better at trail running, your priority in training should be practicing running on trails. In order to get better at ultrarunning, you priority in training should be practicing running a lot.

So, while there certainly may be benefits of weight training for trail and ultrarunners, they do not outrank the benefits of specificity, or in this case, running, when it comes to performance. If an athlete chooses to prioritize lifting over running, then this certainly could be considered a negative factor.

Increased Stress/Demands on Body

As far as your body is concerned: physical stress is physical stress. It doesn’t care or differentiate stress that comes from running versus stress that comes from weight training, versus stress that comes from a 6 hour dancing spree in high heels at your best friends wedding.

Adding weight training on top of your trail or ultrarunning training only increases the stress on your body. This, of course, is going to increase your body’s demand for rest, recovery, and fuel (proper nutrition & increased caloric intake). If you can meet those demands, then the increased stress is not necessarily a negative factor.

However, not addressing and meeting the needs of your body to adequality compensate for the increase in physical stress can detract from your overall running.

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)

Have you ever woken up the morning after a heavy weight training session (or maybe your first weight lifting session after taking a long time off) and felt that incredibly sore feeling in your muscles, quick to remind you of what you did the day before?

That’s known as “Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness”, or “DOMS”. DOMS typically begins to develop 12-24 hours after exercise, and may produce the greatest pain between 24-72 hours post workout (1)

The exact cause of DOMS is still widely debated, but it’s widely believed that the soreness develops as a result of microscopic damage to muscle fibers involved in exercise. The severity of DOMS depends on the amount of force placed on the muscle. For example: running downhill for long stretches versus running on flat ground may cause greater DOMS in the quadriceps muscles. Lifting a much heavier weight to achieve a 1 rep max may cause greater DOMS than lifting a lighter weight that your body is used to for 10 repetitions.

Symptoms of DOMS include:

- muscles that hurt with normal movement

- muscles that feel tender to the touch

- reduced range of motion due to pain and stiffness when moving

- swelling in the affected muscles

- muscle fatigue

- short-term loss of muscle strength

A case of DOMS can hinder your running workout. Say you are scheduled for a tempo run as a part of your ultramarathon training, but your legs are so sore from a strength workout 48 hours ago, that you can barely run with a normal gait, never mind hit your tempo pace. Now, you may have gotten in a killer leg day at the gym, but you’ve missed out on an important run workout, which matters most when considering training specificity.

Common Misconceptions About Weight Training for Runners:

Focusing on Light Weights & High Reps

As we already discussed above, the simple rule of thumb is that lifting a heavy weight (relative to YOUR strength) over a low number of repetitions typically results in muscle hypertrophy (increasing muscle mass), and activates Type 2 muscle fibers (“fast twitch”), which have greater power but fatigue quickly, and lifting lighter weights (again, relative to your strength) over a higher number of reps will increase muscular endurance (the ability for your muscle to continuously contract against a given resistance or movement) and will help develop Type 1 muscle fibers (“slow twitch”) that are endurance based and slow to fatigue.

Because long distance running utilizes mainly “slow twitch” muscle fibers, many runners believe they should focus on a light weight, and higher repetition strength training program.

However, time and time again research has shown that for runners, heavy (70-80% of your one rep max [1RM]) and/or plyometric strength training is far superior to low weight, high repetition strength training. (4,9) Do not be afraid to lift heavy!

Strength Training Will Make You Bulky or “Slow”

If I had a dollar for every person who came through my office when I was working full time in a gym setting who said something along the lines of “I want to lift weights, but I don’t want to get bulky…” I could coach all of my athletes for free.

In general, people seem to fear “bulking up” when it comes to weight lifting.

But here’s the reality: growing sizable muscle mass (or, “hypertrophy” of muscle) is really, really hard. It takes a lot of effort, and a TON of calories. Ask any bodybuilder or simply gym enthusiast who is trying to put on size, and they will confirm.

Most people who are not strength training with the sole intent of putting on sizable muscle mass will not “bulk up”, because:

- They simply will not put in enough time in the weight room for this to happen

- They won’t eat the volume of food required for this to happen

- In the case of females, simply don’t have the testosterone levels in order to put on sizable mass.

So, fearing that strength training will make you bulky, and thus, slow you down (because, more mass = more energy required to run) is not necessary.

If you are new to strength training, chances are your body composition will change. However, what’s more likely is that as you put on some lean muscle mass, your overall body fat percentage will drop, as an increase in muscle mass will also increase your metabolic requirements. Further, lean muscle mass is more dense than adipose tissue, meaning that one single pound of muscle will take up less space in your body compared to one pound of fat.

How to Combine Running and Strength Training for Trail & Ultra Runners

If you’ve made it this far and have decided that you would like to incorporate strength training into your trail and/or ultramarathon training, I highly encourage you to keep the following things in mind:

Remember Specificity

The number one thing I want you to remember before diving into a strength training program and pairing it with ultra training, is that the strength should HELP, not HINDER your running or ultramarathon goals.

Bottom line: specificity matters. If it comes down to having to choose one over the other, choosing your running workouts matters MORE in the case of training for trail running or ultramarathon success.

On that note, I always recommend that my clients perform their running workouts FIRST, before their strength training. This not only guarantees that the workout gets done, if time availably becomes an issue, but ensures that a heavy or hard strength workout won’t negatively affect a run later in the day.

Start at the Beginning OR during Off-Season

Start your strength training cycle at the beginning of your ultramarathon training cycle, or better yet, during off season before diving into a race specific training program.

In other words: deciding just a few weeks before the race that you’d like to lift weights is probably not a good idea.

Starting early will allow you to ease into the stressors of strength training while your running volume is still low, keeping the overall stress level manageable.

On that note, if you’re brand new to strength training, or simply not entirely confident with lifting weights, I highly recommend seeking out professional help to ensure you are performing each exercise with proper form. That can vary from hiring a one-on-one personal trainer, to simply seeing if your local gym offers an introductory class or complimentary session to help you familiarize yourself with the equipment.

Emphasize Recovery

A common belief among the ultramarathon and endurance running industry is that there is no such thing as “overtraining”, but rather, athletes under-fuel and under-recover for the level of stress placed on their bodies.

Remember that adding strength training in addition to your ultramarathon training is going to increase your body’s demand for rest, recovery, and fuel (proper nutrition & increased caloric intake). Give you body what it needs, as far as sufficient nutrition and plenty of rest.

Balance Weight Training Goals with Trail or Ultrarunning Goals

As with anything, consistency matters. For the best results, you’ll want to continue strength training throughout your trail or ultramarathon training cycle. However, you’ll want to find a careful balance between your strength training and running, so that the stimulus of one doesn’t detract from the other.

For example, lifting until failure or attempting to set one-rep max PR’s while simultaneously trying to push through the peak volume of a 100 mile ultramarathon training plan could be disastrous.

Plan your strength training cycle around your trail or ultrarunning goals, both during any given week, and across the entire training cycle as a whole.

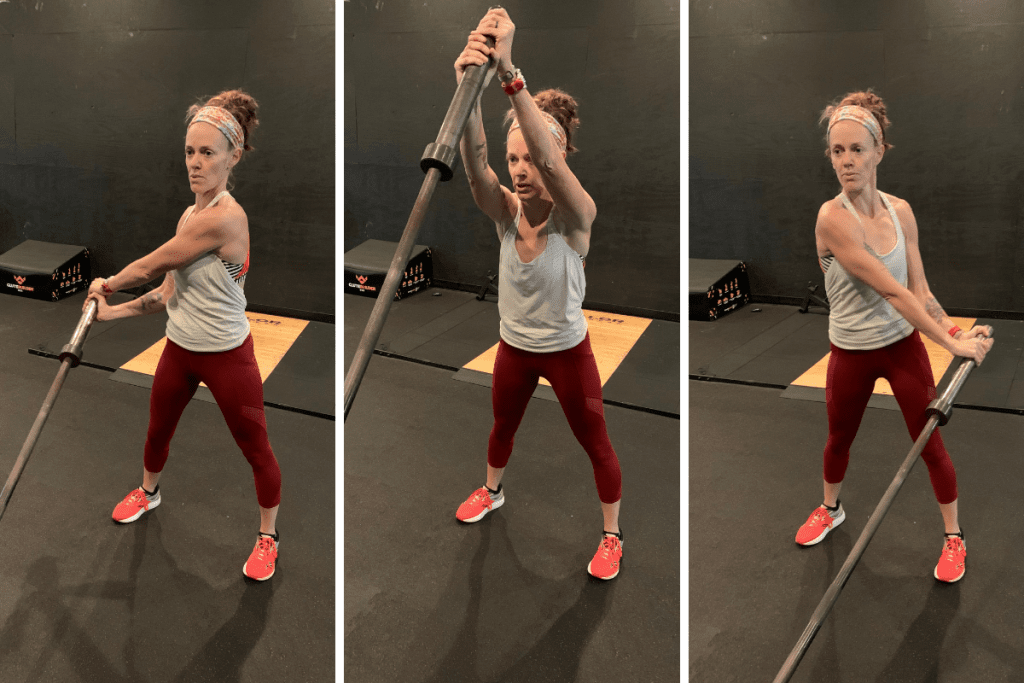

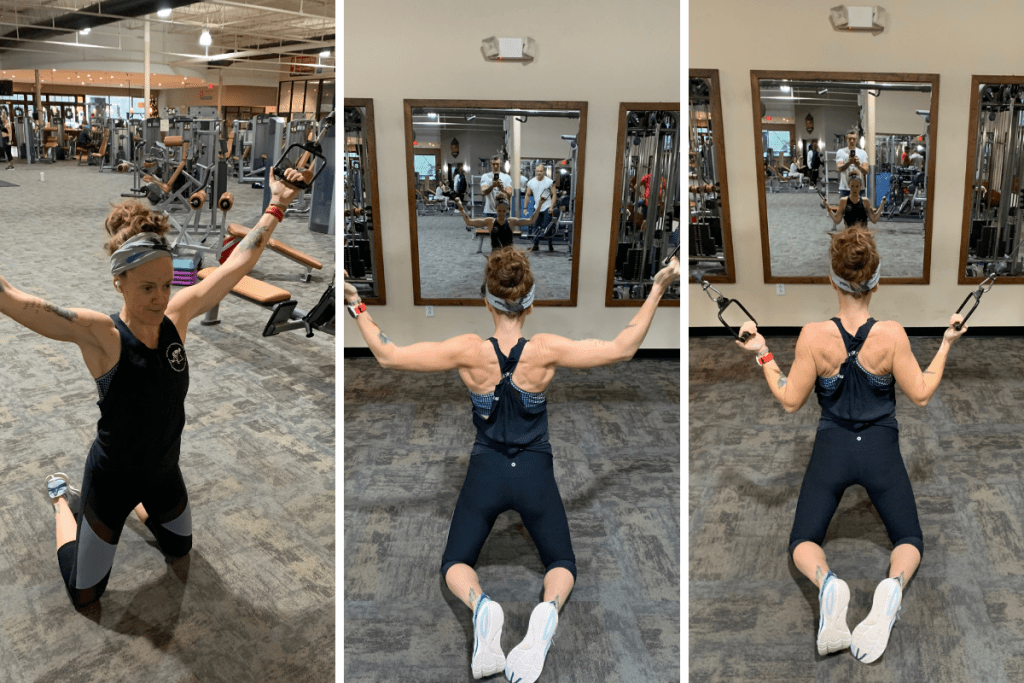

For more on how to balance your strength training and ultramarathon goals, check out the post: Simplifying Strength Training for Ultrarunners: 7 Moves to Balance Lifting & Running

Final Thoughts:

Plenty of runners are indeed successful without incorporating strength training into their lives. However, I’m willing to bet that the majority (if not all) of you reading this post are not elite athletes. You are everyday runners who have more to worry about than your race finishing times.

Things like: family, careers, loved ones, and staying healthy for years to come.

In my professional opinion, the everyday health benefits alone of strength training should be sufficient reason to encourage you to pick up some weights from time to time.

Resources:

- American College of Sports Medicine (2011) ACSM information on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/delayed-onset-muscle-soreness-(doms).pdf?sfvrsn=8f430e18_2

2. Bahr R, Krosshaug TUnderstanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sportBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;39:324-329.

3. Balsalobre-Fernández, C., Santos-Concejero, J., & Grivas, G. V. (2016). Effects of Strength Training on Running Economy in Highly Trained Runners: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 30(8), 2361–2368. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001316

4. Berryman, N., Mujika, I., Arvisais, D., Roubeix, M., Binet, C., & Bosquet, L. (2018). Strength Training for Middle- and Long-Distance Performance: A Meta-Analysis. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 13(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0032

5. Blagrove, R. C., Howatson, G., & Hayes, P. R. (2018). Effects of Strength Training on the Physiological Determinants of Middle- and Long-Distance Running Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 48(5), 1117–1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0835-7

6. Ferber, R., Hreljac, A., & Kendall, K. D. (2009). Suspected mechanisms in the cause of overuse running injuries: a clinical review. Sports health, 1(3), 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738109334272

7. Harvard Health. (2016, February 19). Preserve your muscle mass. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/preserve-your-muscle-mass

8. Kasper, Korey MD Sports Training Principles, Current Sports Medicine Reports: April 2019 – Volume 18 – Issue 4 – p 95-96 doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000576

9. Li, F., Nassis, G. P., Shi, Y., Han, G., Zhang, X., Gao, B., & Ding, H. (2021). Concurrent complex and endurance training for recreational marathon runners: Effects on neuromuscular and running performance. European journal of sport science, 21(9), 1243–1253. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1829080

10. Shaw I, Shaw BS, Brown GA, Shariat A (2016) Review of the Role of Resistance Training and Musculoskeletal Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation. J Orthop Res Ther 2016: 102. DOI: 10.29011/2575-8241.000102

11. Westcott, Wayne L. PhD Resistance Training is Medicine, Current Sports Medicine Reports: July/August 2012 – Volume 11 – Issue 4 – p 209-216 doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825dabb8

Heather Hart is an ACSM certified Exercise Physiologist, NSCA Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), UESCA certified Ultrarunning Coach, RRCA certified Running Coach, co-founder of Hart Strength and Endurance Coaching, and creator of this site, Relentless Forward Commotion. She is a mom of two teen boys, and has been running and racing distances of 5K to 100+ miles for over a decade. Heather has been writing and encouraging others to find a love for fitness and movement since 2009.

Erin

Heather, thanks for this! I’ve anecdotally noticed weight lifting improving my trail running paces and it was interesting to read why. Appreciate the research and easy-to-read breakdown!

Ted Williamson

Excellent material, Heather! I come from a weight training background but have not done much of it since I started serious running 13 years ago. Now at age 64 I find that, though I can still be competitive both overall and within my age group (my latest 100M finish this January was 21:41), I have become more concerned about declining muscle mass and bone density as I age. So that alone has me researching this topic. The past week I started with some basic core strengthening of standard planks and side planks along with pushups and ab work. It was the pushups that made me realize just how pathetically weak my upper body had become and reinforced the need for me to get back to weight training. My questions now revolve around which specific movements to use in the weightroom to achieve an optimal balance that enhances my running while achieving increased muscle strength and mass and bone density. For the moment I’ll go back to the basic movements I’m familiar with for arms, back, chest, abs, legs(?), etc. just to get back into the swing of weight training. And combine what I already know about weight training with basic core strength and hip mobility/flexibility work and adjust with what I discover going forward. I have no concerns about getting huge because I understand your point about what is required for that to happen. I’m actually looking forward to reactivating those long underused muscles and seeing just how much (if any) memory still resides within. All the above said, I would appreciate further discussion or referral to material on the best movements to focus on in the weight room (along with those that should be avoided) for optimal running and to meet my other goals. Thank you!

Heather Hart, ACSM EP

Hi Ted! Thank you so much for your compliments, and for taking the time to comment! It is never too late to add strength training back into your training, so I’m always glad to hear when a runner intends to do so. Regarding further discussion on the best movements, I’ll point you in the direction of this post: https://relentlessforwardcommotion.com/simplifying-strength-training-for-ultrarunners/ It’s long and detailed (probably too long, I’m trying my best to learn how to get to the point!) but more specifically, I believe this table might help you out: https://relentlessforwardcommotion.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Final-Strength-Training-for-Ultrarunners-Tables.png If you have any more questions, feel free to continue the conversation via this comment thread, or send an email to me directly at [email protected] Best of luck with your strength training goals!!

Heather Hart, ACSM EP

p.s. I will add that even though the post is titled “Strength Training for Ultrarunners”, this 7 move concept is beneficial for runners of any distance looking to increase their strength.

Ted Williamson

Thanks Heather. I’ll check out the links you’ve provided. My next BIG race is Badwater 135. I ran the 135 along with the other two Badwater races (Cape Fear & Salton Sea) in 2019 and am happy to have been selected again for 2022. Just got back from my first gym visit in over 2 years. I’m very aware of DOMS so I took it very easy. Excited to reactivate those dormant muscles once again and look forward to the benefit my running is sure to derive from the effort. Thanks again and take care. Cheers!