Last Updated on January 31, 2022 by Heather Hart, ACSM EP, CSCS

If you’ve been around the endurance community long enough, chances are you’ve heard the term “VO2max” thrown around. Further, if you own a newer GPS watch, you may have even seen a number assigned to you as your VO2 max.

But what exactly is VO2 max? What does that number mean for you as a runner, and can your watch REALLY tell you your VO2 max? In this post we’ll dive into the basics of VO2 max and running, and explain why this measurement matters – or doesn’t – to runners.

What is a VO2max Measurement?

VO2 max is a measurement of the maximum rate of oxygen consumption measured during incremental exercise. This number, typically between 30-60 (though elite athletes often test between 70-80 or more), is measured in milliliters of oxygen per minute per kilogram of body weight (ml/min/kg).

Let’s break that down in easier to understand terms: VO2 max refers to the maximum amount of oxygen your body can take in and use during exercise.

(VO2 max is not to be confused with lacate threshold, which is an entirely different measurement. But, lactate threshold occurs at a percentage of VO2 max (typically LT occurs at 80-90% of VO2 max, but this can vary by individual). The amount your lactate threshold can increase is dependent upon the ceiling of your VO2 max. Therefore, it’s useful for runners looking to improve their performance to focus on training both systems.)

Before we can really understand what VO2 max is, and why (or why not) it matters to runners, we’ve got to dive into some very basic human anatomy and physiology. Bear with me, this will all make sense soon enough:

Why We Need Oxygen:

You don’t need a degree in science to understand that oxygen is essential for human life. From the time we are little we understand that if we stop breathing, for whatever reason, we die.

But do you know exactly WHY we need oxygen?

Oxygen is a necessary component of cellular respiration. Cellular respiration is the process by in which our bodies break down sugar (from the foods you eat) and turn it into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Think of ATP as the body’s useable form of energy. ATP is then used to perform work at the cellular level (i.e. “do” all of the things your body needs to do to continue living).

Obviously, the various energy pathways in which we create fuel, both with and without oxygen, are much more complicated than that, but for the purpose of this blog post, this is what you need to know:

Cellular respiration provides cells with the energy they need to function. So, without oxygen, eventually cellular respiration eventually stops (as anaerobic pathways are not infinite). The result: no more energy to “fuel” your cells. And when your cells run out of fuel, they stop working, and your body shuts down.

What Happens When We Breathe?

Now that you understand why we need oxygen, let’s talk about how we get oxygen in the first place.

By breathing, of course. But it’s slightly more complex than that (of course it is!).

The “air” we take in through our nose and mouth with each breath is actually made up of a mixture of different gases. The air in Earths’ atmosphere is made up of about 78 percent nitrogen, 21 percent oxygen, and that last 1% is a combination of argon, carbon dioxide, neon, helium, methane, and krypton.

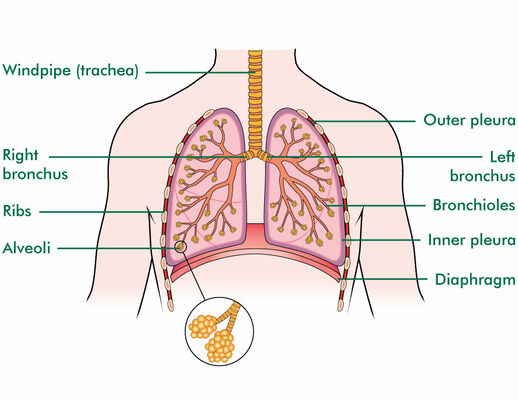

When we take a breath, air rushes into our lungs. Now, we may think of our lungs as big, inflatable organs, but there’s a lot of structure within the lung itself. Bronchial tubes branch into thousands of thinner tubes called bronchioles. The bronchioles end in clusters of tiny air sacs called alveoli. Alveoli are made up of a mesh of tiny blood vessels called capillaries.

It’s at these capillaries where gas exchange occurs: oxygen from the air you breathe is filtered into the blood, to be shuttled throughout your body via a protein called hemoglobin.

Further, carbon dioxide and water (in the form of water vapor), waste products of cellular respiration, are filtered out of the blood and back into your lungs, to be exhaled back out into the air.

Oxygen’s Role in Running

Now that you understand how we get oxygen, and what we use it for, let’s talk about oxygen and running. When you run, your muscles work harder. Remember, your cells need oxygen to produce energy. So as a result of working harder, your body uses more oxygen and produces more carbon dioxide.

This explains why you breathe harder, and your heart beats faster when you run: your body is working harder to supply oxygen to your cells to gain more energy, and simultaneously getting rid of the waste products (CO2 and water).

The greater your VO2 max, the more oxygen your body can consume (use per breath), allowing your body can use that oxygen to generate the maximum amount of ATP energy.

Related post: Cardiovascular Drift and Running – What Runners Need to Know

VO2 Max and Running explained:

So far we’ve covered:

- Why our bodies need oxygen

- Why our bodies need even MORE oxygen when we run

- What exactly happens when we breathe (how we get our oxygen)

But now we’re ready to come full circle and actually discuss VO2 max and how it applies to runners. Remember, at the beginning of the post we explained that VO2 max refers to how much oxygen your body can absorb and use during exercise. So, in theory:

- The greater your VO2 max, the more oxygen your body can consume.

- The greater your VO2 max, the more effectively your body can use that oxygen to generate the maximum amount of ATP energy. *

- The more energy available, the harder (or longer) your body can continue to run.

(* see paragraph on Running Economy towards the end of this post.)

How is VO2max Accurately Measured?

In order to accurately measure VO2 max, you must directly measure the volume and gas concentrations of inspired and expired air. This involves some serious, high tech equipment (a metabolic cart), which is why you typically only see VO2 max tests performed in a scientific lab or private practice.

A VO2 max test involves putting an athlete on either on a treadmill or a bike at an intensity that increases every few minutes until exhaustion (meaning: that “I might puke and pass out” point, not even kidding), and is designed to achieve a maximal effort. The athlete wears a mask, connected to the metabolic cart, to measure the inhaled and exhaled air, determining the amount of oxygen consumed with each breath.

If you’ve never had the pleasure of participating in a VO2 max test let me assure you: they are miserable. Which, for many of us, brings us some strange sort of pleasure, but I digress.

Can my Running Watch Accurately Measure my VO2 max?

As you may have guessed by this point, a watch you wear on your wrist is not measuring the amount of oxygen you inhale and comparing it to the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide you exhale. Therefore, no, you running watch can not accurately measure your VO2 max.

So instead, your watch is using “sub-maximal” exercise protocols that estimate VO2 max based on the relationship between your heart rate and pace. But is this very accurate?

One research study out of Eastern Michigan University tested 23 participants, using both a a treadmill/metabolic cart VO2 max test and a Garmin Forerunner 235 to measure VO2 max. The results showed the the average VO2 max in the lab was 52.4 ml/kg/min, compared to 49.3 ml/kg/min with the watch. This particular study concluded that the GPS sports watch was not a valid estimate of VO2max. (Pearson et al, 2017)

How to Calculate Your VO2 Max

There are a number of submaximal field tests you can do to calculate your VO2 max if you do not have access to maximal testing options at a lab. It’s improtant to remember that the VO2 max numbers you calculate at the end of these tests are simply estimates.

The Cooper 12 Minute and 1.5 mile tests were designed by Dr. Kenneth Cooper in the late 1960’s, and have withstood the test of time. Numerous studies have shown that both tests are useful alternatives to estimating VO2 max when a lab test is not feasible (Mayorga-Vega et al, 2016).

Safety Note: The Cooper 12 Minute and the 1.5 Mile Run tests are intended for individuals who are apparently healthy and regularly physically active. Always consult your physician before beginning a new workout routine.

Cooper 12 Minute VO2 Max Test Protocol

To perform the Cooper 12 minute VO2 max test, you’ll need a flat and accurately measured surface such as a standard 400-meter outdoor track, or a treadmill. You’ll want to perform the test during a time of day where weather conditions are relatively mild.

Test instructions:

- Start with a warm-up of about 10 minutes.

- For the test, start your watch at the beginning of your 12 minute run

- Run as fast/hard as possible for 12 minutes. You want to try to maintain a steady pace throughout the test while covering as much distance as possible. A common mistake in this test (and many running tests) is to start much too fast. This will result in early exhaustion and will cause you to slow down considerably the rest of the way.

- At the 12 minute mark, hit “stop” on your watch, and note your distance (or number of laps covered).

- Continue with a cool down for about 5-10 minutes

Use the following equation to estimate your VO2 Max from the 12 minute test:

VO2 max (mL/kg/min) = (distance in meters -504.9)/44.73

Cooper 1.5 Mile VO2 Max Test Protocol

To perform the Cooper 1.5 Mile VO2 max test, you’ll need a flat and accurately measured surface such as a standard 400-meter outdoor track, or a treadmill. You’ll want to perform the test during a time of day where weather conditions are relatively mild.

Test instructions:

- Start with a warm-up of about 10 minutes.

- For the test, start your watch at the beginning of your 1.5 mile run.

- Run as fast/hard as possible for 1.5 miles. You want to try to maintain a steady pace throughout the test while covering as much distance as possible. A common mistake in this test (and many running tests) is to start much too fast. This will result in early exhaustion and will cause you to slow down considerably the rest of the way.

- Once you hit 1.5 miles (2.4 km) hit “stop” on your watch and record your time.

- Continue with a cool down for about 5-10 minutes.

Use the following equation to estimate your VO2 Max from the 1.5 mile test:

VO2 max (mL/kg/min) = (483 / time in minutes) + 3.5

VO2 Max Norms for Runners

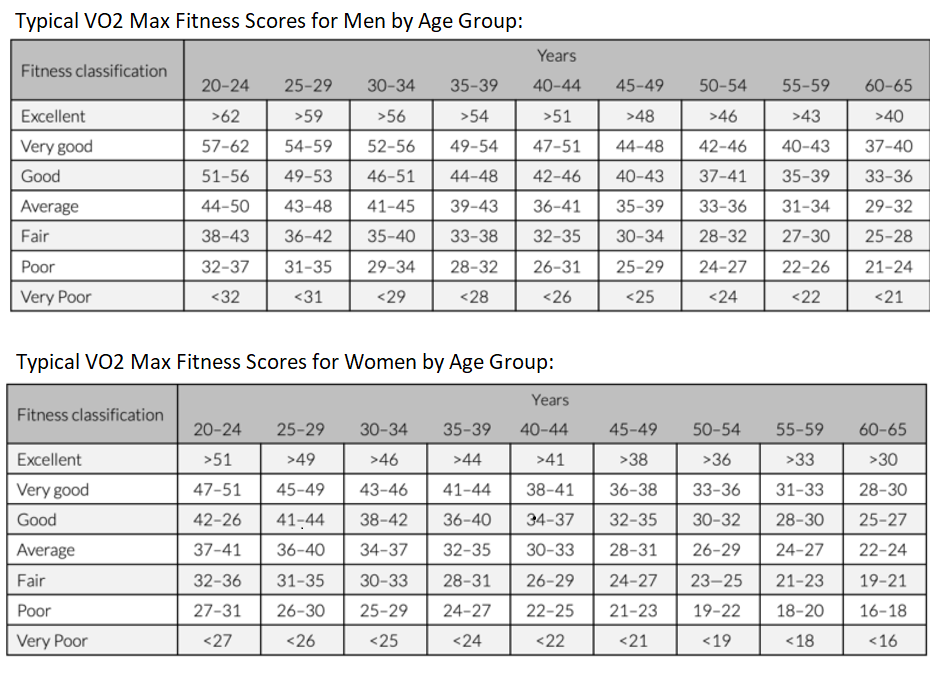

So, where do your VO2 max results fall on the norms for runners? Compare to this chart below, adapted from the information provided by the Cooper Institute:

Can I Improve My VO2 Max?

You absolutely can increase your VO2 max, to an extent, through…you guessed it: exercise!

According to UC Davis Health Sports Medicine department: “Regular training results in an increase in the efficiency of oxygen transport within the body. By lowering the resting heart rate (HR), and the HR at sub maximal loads, the heart pumps more blood with every heart beat. This, in addition to other physiological changes, increases the oxygen extraction capability.”

In simpler terms, practice makes perfect, and that goes for the ability of your body to consume oxygen to create energy.

How MUCH Can I Increase My VO2 Max?

The amount in which a runner can increase their VO2 max is dependent on many variables (see the limiting factors below. ) The percent increase varies considerably from person to person, ranging from 5-30%.

In general, people who are the least fit see the largest changes, and athletes who are highly fit see the smallest changes in VO2max due to training.

VO2 Max Limiting factors:

The following may affect your VO2 max ceiling, as well as how much room you have to improve your personal VO2 max:

- Age: VO2 max scores typically peaking by age 20 and declining by nearly 30% by age 65.

- Gender: Males typically have a higher VO2max compared to females with similar training & competition level

- Genetics: Researchers estimates that around 50% of an individual’s maximal oxygen uptake is determined by genes. This may be related to hemoglobin level, heart structure, size, and function, and the capacity of skeletal muscle to utilize oxygen.

- Altitude: Athletes generally have a 5% decrease in VO2 max results for every 5,000 feet gained in altitude. This is due to the fact that the barometric pressure of the atmosphere is significantly less at high altitude. The result is that oxygen molecules in the air are further apart, reducing the oxygen content of each breath incrementally as one goes up in altitude.

The Best VO2 max Running Workouts for Improving Maximum Aerobic Capacity:

If you want to attempt to increase your maximum aerobic capacity, there are a number of studies (such as this one from Dr. Helgerud, et al, out of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology) that demonstrate that interval training at 90-95% of maximum heart rate is the best approach to take.

To learn more about the Best VO2 max workouts for runners, visit my full post “VO2 Max Interval Workouts for Runners”

Does VO2max Even Matter to Runners?

Let’s finally answer the important question: does your exact Vo2max even matter to you, as a runner?

Maybe.

I bet you weren’t expecting that, but hear me out here. VO2max is simply a measurement. Yes, it’s a good indicator of aerobic fitness. But what might be a better indicator of performance than VO2 max when it comes to runners is your running economy.

Running Economy

Where VO2 max measures the maximal levels of oxygen consumption at peak intensity, running economy measures the amount of oxygen that’s actually used to carry you forward while running at submaximal levels – or, the actual paces you are typically running on a daily basis.

Running economy measures how physiologically efficient your body is. That takes into account so much more than just oxygen consumption. It also involves other important physiological adaptations such as:

- metabolism (how efficient is your body at making and using stored energy?)

- biomechanics (how well does your body move when running?)

- mitochondrial capacity in your muscles (how well do your muscles actually use the oxygen your body delivers?)

- neuromuscular considerations

In other words: VO2max measures how much oxygen your body can consume during exercise, but running economy measures how much oxygen your body actually NEEDS, and how well it uses the oxygen.

And just like a car with good gas mileage: the less energy and oxygen you use to go the same distance, the better.

Point being? You can have a great VO2max thanks to genetics, but if you’ve never run a step in your life, you’re not going to be the best runner out there. Sticking with the car analogy: you can have a great engine, but if you have flat tires and rusty axles, you aren’t going to win the race.

High VO2 max = Decreased Running Economy?

Science is still unclear as to whether there’s a trade-off between having a high VO2 max, which means you’re able to burn through aerobic energy at a very high rate, and having good running economy, meaning you get the most out of each unit of aerobic energy that you burn. So when it comes to longer distance endurance athletes, such as ultrarunners, a high VO2max can potentially be hindering. (Joyner, 1991 and Nilson et al, 2019)

VO2 Max and Running: Final Thoughts:

Holy cow, is your head spinning yet? I hope that this post discussing VO2 max and running brought some insight into what the heck VO2max means on a very basic, surface level explanation. But if it’s left you even more confused than before, here’s the one take away I want you to understand:

Your running is not defined by numbers.

There is absolutely merit to using these numbers to track improved progress, even if they aren’t exactly accurate, if that’s what you are going for. But ultimately:

You are no less of a runner if your mile PR is 14 minutes than if it were 4 minutes.

You are no less of a runner if your longest long run is 5 miles, compared to someone who easily logs a Saturday 25 miles.

And you are no less of a runner if your VO2max is less than that of a running friend.

Oh, and p.s. – the VO2max value your watch has given you probably isn’t accurate anyway.

Heather Hart is an ACSM certified Exercise Physiologist, NSCA Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), UESCA certified Ultrarunning Coach, RRCA certified Running Coach, co-founder of Hart Strength and Endurance Coaching, and creator of this site, Relentless Forward Commotion. She is a mom of two teen boys, and has been running and racing distances of 5K to 100+ miles for over a decade. Heather has been writing and encouraging others to find a love for fitness and movement since 2009.

Leave a Reply