Last Updated on January 11, 2023 by Heather Hart, ACSM EP, CSCS

I spend a lot of time around here trying to convince runners of all of the amazing reasons why they should include strength training alongside their running. But I’ve yet to address the other half of the crowd – those who love strength training, but also want to run.

Much like asking a parent to choose a favorite child, when it comes to running or strength training, I currently cannot declare a greater love for one over the other. I love to run, I love to lift, and I regularly participate in both.

Similar to the misunderstandings among the running crowd when it comes to lifting (such as, only doing super high reps, or fearing that resistance training will make them “bulky” and “slow”), there are misunderstandings among the lifting crowd when it comes to running. Common questions I’m asked include “does running burn muscle?” and “does running kill my strength training gains?”

In this post we’re going to dive into the science – in an easy to understand way – behind how running can affect your progress in the weight room.

What is Hybrid or Concurrent Training?

Concurrent training (often referred to as hybrid training) refers to combining exercise modes that utilize differing energy pathways (phosphagen, aerobic, and anaerobic), either in the same workout, close together in succession, or simply in an overall training mesocycle.

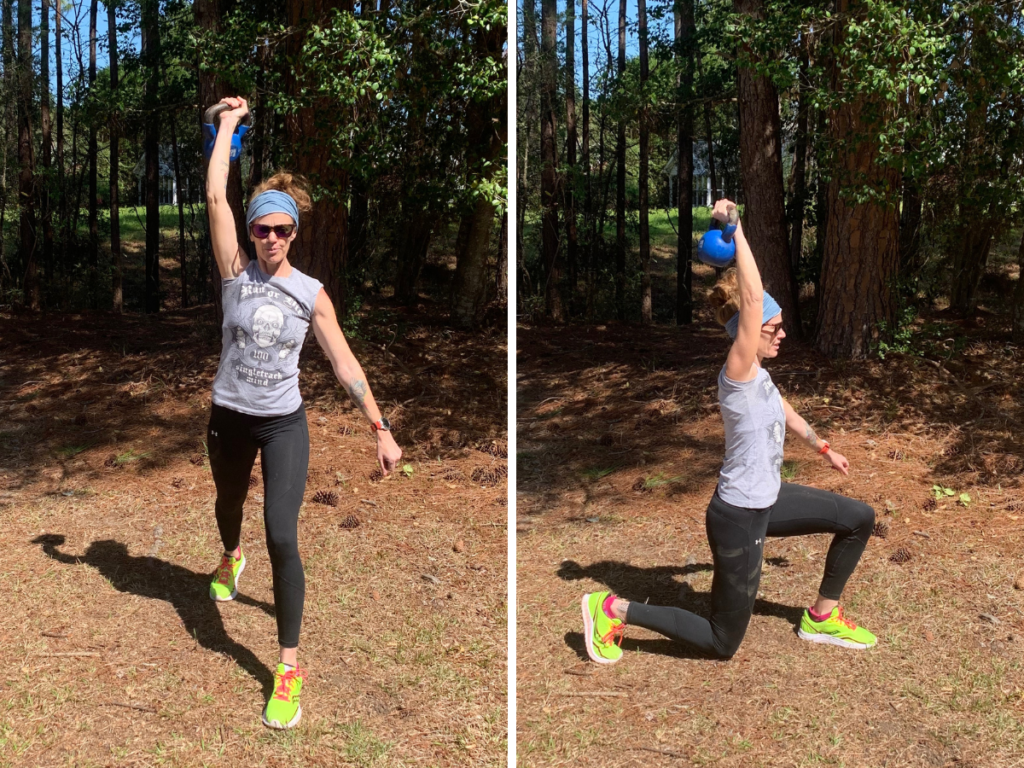

In more practical terms: concurrent training refers to combining a lower intensity cardiovascular exercise – such as running – with a higher intensity, anaerobic exercise – such as strength training.

Have you ever gone to the gym and knocked out an easy 3 miles on the treadmill before diving into a heavy leg day? That is concurrent training.

Is Concurrent Training Recommended?

Current general guidelines for optimal health recommend that all healthy adults participate in concurrent training, with the goal of a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity cardiovascular exercise (or 75 minutes of vigorous cardio), as well as days of muscle strengthening/resistance training exercise per week.

However, when it comes to more specific training for sport performance and fitness goals beyond general health, science isn’t entirely sure if concurrent cardiovascular exercise (like running) has a negative effect on resistance training.

Numerous studies have shown that concurrent training may result in decrements in strength, power, and muscular hypertrophy (more on this below). But, seemingly just as many other studies provide evidence showing that endurance training and resistance training does not inhibit strength or muscular gains.

More recently, in 2021 researchers published an updated review and meta-analysis of 43 studies, including 1,090 participants, to try and assess the compatibility of concurrent aerobic and strength training in regards to adaptations in muscle function (maximal and explosive strength) and muscle mass, compared to strength training alone.

Their findings showed that:

- Concurrent aerobic and strength training does not interfere with the development of maximal strength and muscle hypertrophy compared with strength training alone, regardless of the type of aerobic training (cycling vs. running), frequency of concurrent training, participant training status (untrained vs. active), or age of participant.

- However, researchers did find evidence of reduced development of explosive strength with concurrent training, particularly when aerobic and strength training were performed in the same session. (8)

In April of 2022, these same researchers conducted another review/meta-analysis, this time of 15 studies (300 participants), this time to determine how much concurrent aerobic and strength training, compared with strength training alone, influences type I and type II muscle fiber size adaptations.

Their findings this time around showed that there was indeed an inhibition in hypertrophy of type I fibers only (but not necessarily a difference in whole muscle hypertrophy) when aerobic training was performed by running, but not cycling (Lundberg)

Does Running Burn Muscle?

So let’s get right to the burning (but not due to lactate, and that’s a soapbox for another day) question: does running actually burn or breakdown muscle?

Yes…sort of. But not in the way so many misinformed running-nay-sayers at the gym or your local CrossFit box may have led you to believe.

Net Muscle Protein Balance:

Muscle proteins are constantly being broken down and rebuilt within your body. Muscle protein breakdown naturally occurs during exercise: it’s an important metabolic component of muscle remodeling, adaptation to training, and increasing muscle mass.

Break it down, build it back stronger than before.

While this entire process is carefully regulated by your body, muscle protein breakdown is greatly influenced by things such as exercise type, duration, and intensity, as well as nutritional status (i.e., what and how much you eat).

So yes, when you run, your body is breaking down muscle proteins. But to be fair (insert “to be faiiiiir” GIF here, for all of my Letterkenny fans) this isn’t exclusive to running, it happens during all modes of exercise.

Muscle Protein Breakdown vs. Muscle Protein Synthesis

During exercise, while muscle protein breakdown increases, muscle protein synthesis slows down. Meaning: at the end of a workout, your net muscle protein balance is actually negative.

Gasp! You’ve (in theory) lost muscle!

Have no fear: the good news is that immediately after exercise, muscle protein synthesis-the process where your body rebuilds muscle – rebounds, for upwards of the next 48 hours. Assuming your diet is adequate in protein and carbohydrates (and that you’ve eaten recently or immediately post exercise), your body will use amino acids (the “building blocks of protein”) to replace and rebuild what was lost, bring your net muscle protein balance back to zero.

In the case of running, your body not only brings the net muscle protein balance back to zero, or even positive (if you are newer to running/exercise), but it remodels the muscle towards a more oxidative phenotype and increasing mitochondrial density – meaning it becomes better adapted for running. (3)

Regular resistance training stimulates muscle protein synthesis to the point where, in the presence of amino acids from adequate protein consumption, your body will replace and exceed the protein breakdown from exercise, resulting in a positive net muscle protein balance. Which, you guessed it, equals muscular growth.

Protein as an Energy Source:

Now, let’s talk more specifically about running “burning” muscle, in the sense of using it as an energy source.

Without going totally overboard (I’m getting better at this, I think…) let’s talk about energy sources. Our bodies use the food we eat to create a usable source of energy to fuel almost everything we do. Food consists of three macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

During aerobic exercise – like running – our body prefers to use carbohydrates. Of the three macronutrients, protein provides the least significant contribution to total energy. However, there are two situations when protein contributions towards energy requirements will increase while running:

- During a prolonged run (around 90 minutes or more).

- When there is not enough available glycogen for ATP production.

In these cases, muscle protein can be broken down into amino acids, which can then be used to create ATP, contributing upwards of 3-18% of the body’s energy requirements (2).

Other Reasons Why Running May Affect Strength Training Gains

“Burning muscle” aside, let’s take a look at a few of the believed theories as to why running may affect improvements in strength training.

1. Interference Effect

One of the most common theories behind how running or other aerobic exercise may affect strength training is known as the Interference Effect, or the Concurrent Training Effect.

As we already discussed in the muscle protein breakdown vs. muscle protein synthesis section above, exercise – whether it’s cardio or resistance training, aerobic or anaerobic – places stress upon our bodies that results in growth and adaptation on a cellular, structural level. This is how we get faster/stronger/bigger/better/etc.

Our bodies have two main molecular pathways for this cell metabolism and growth when it comes to making adaptations to exercise: mTOR (Mammalian Target of Rapamycin [which currently ranks in my top ten favorite exercise science words/phrases to say, as it sounds like some kind of dinosaur]) and AMPK (Adenosine Monophosphate-activated Protein Kinase).

The mTOR pathway is activated during anaerobic based, well fed/nutrient rich conditions like strength training, and plays a big role in muscle muscle fiber adaptations, such as hypertrophy, or gains in maximal strength development.

The AMPK pathway is activated during aerobic based, energy depleted states like – you guessed it – running long distances. The AMPK pathway stimulates energy production, by signaling the body to increase glucose uptake, as well as oxidation of fatty acids, in order to create more ATP, or energy for the cells to use, as a lot of energy is needed for these sustained activities.

Further, and more important to the topic at hand, AMPK inhibits processes that consume energy, such as protein and lipid synthesis. In short, protein synthesis is how your body produces protein in order to repair muscles damaged from exercise, so that they grow bigger and stronger.

With concurrent training , such as running and lifting, the AMPK pathway downregulates, or inhibits, the mTOR pathway (which, remember, is necessary for those strength training “gains”).

Therefore, the Interference Effect theorizes that combining cardiovascular exercise (like running) and strength training too closely together (or in the same training session) MAY eventually result in diminished returns.

Meaning: yes, your run might be negatively affecting your strength training potential.

2. Poor Management of Training

Greater training volume and training loads put greater stresses on your body. And that increased stress requires greater nutritional requirements, as well as greater recovery.

Inadequate rest and recovery periods between workouts, combined with energy deficiency from not eating enough, can result in fatigue. Fatigue will have a huge impact on the quality of your workouts, as well as your body’s ability to recover from the workouts.

Simply put: less than stellar workouts and crappy recovery will inhibit potential “gains”. To make the most of your workouts, make sure you are balancing them properly.

3. Prioritizing Running Over Strength Training

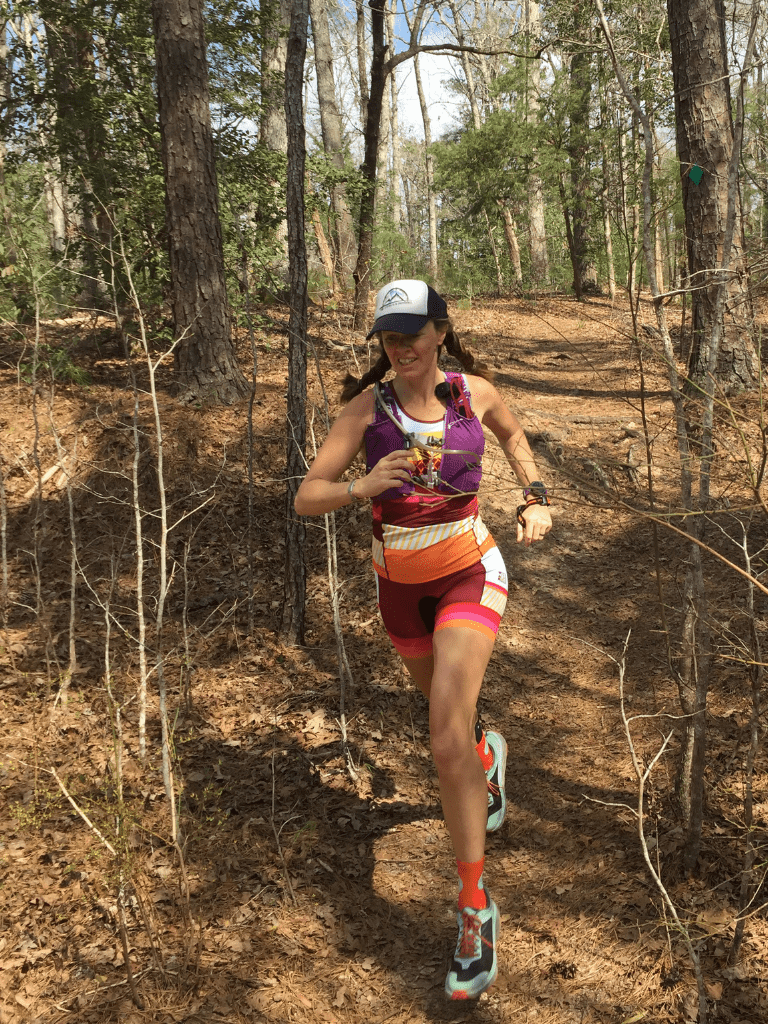

Let’s address the elephant in the room: if running doesn’t “burn” muscle (in the way many believe) or truly inhibit muscular hypertrophy, why are so many elite distance runners so lean, with seemingly lower muscle mass than other athletes?

The answer is simple: specificity.

Elite runners run a lot, likely spending much more time to running than they do to lifting weights. Research shows that single-mode aerobic training like running does not promote the same skeletal muscle hypertrophy as resistance training.

The same goes for non elites: if you prioritize running over strength training, then you simply won’t reach your strength training potential. Please know, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this…it’s just another way running can, in fact, affect strength training gains.

(The other possible reason elites are so lean: a genetic predisposition to a higher percentage of slow twitch [type I] muscle fibers over fast twitch [type II], which generally are smaller cross-sectionally)

Practical Recommendations for Adding Running to Strength Training:

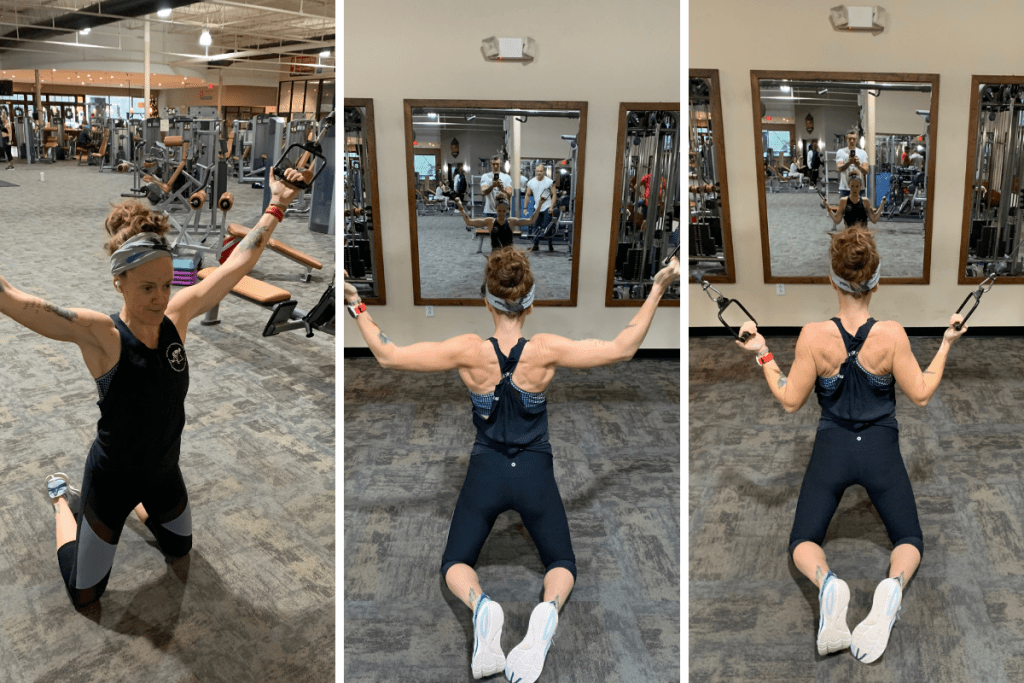

Conflicting evidence in the sports science world can leave athletes feeling uncertain if they are taking the right approach to training. So, if you’re looking to add running on top of your strength training, OR, if you’re a runner who is currently hoping to focus on or prioritize strength/muscular improvements, here’s a few tips to keep in mind:

Timing of Workouts

Spacing your running and strength workouts out may help minimize any possible negative effects of concurrent training by:

- Minimizing the Interference Effect, especially when the workouts involve the same muscle groups.

- Providing enough recovery time to minimize fatigue, ensuring higher quality workouts

- Allowing time for post workout fueling, ensuring sufficient nutrients for both protein synthesis and energy production.

How Long Should You Wait Between Running and Strength Training?

Studies suggest that a 24 hour recovery period between running and strength training workouts in order to obtain full neuromuscular and oxidative adaptations to training (7)

However, this isn’t necessarily a practical approach to athletes who want to incorporate both types of training. Therefore, a minimum of 6 hours of rest is recommended between training sessions. (7)

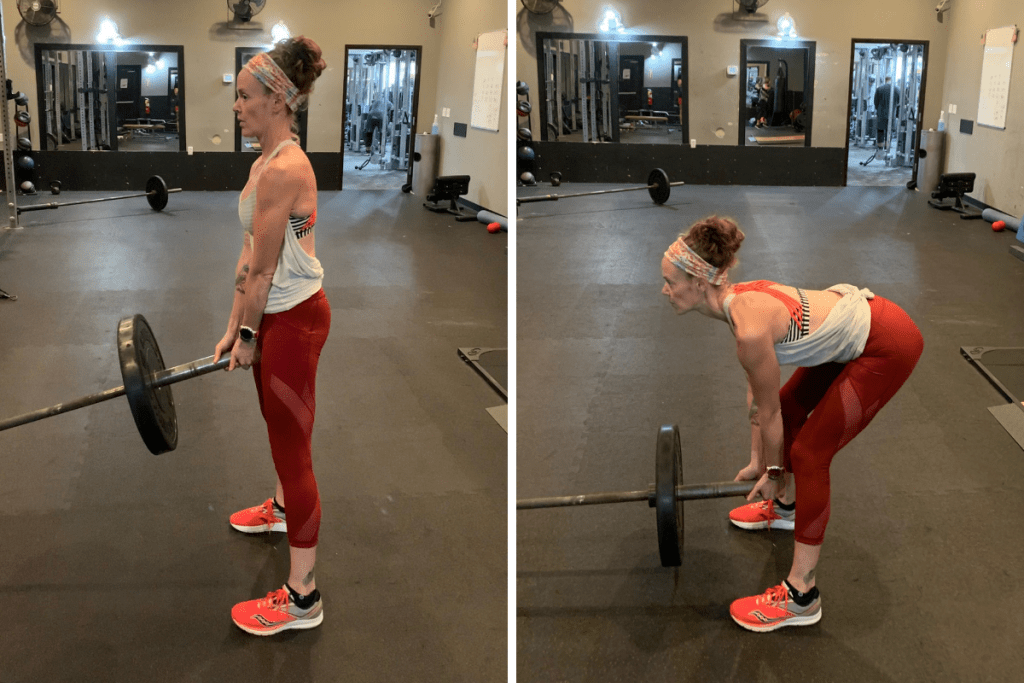

Frequency of Workouts

If you are currently prioritizing any sort of muscular hypertrophy, strength, or power gains over endurance, studies suggest a ratio of 2:1 or 3:1 between resistance training sessions per week: endurance training sessions per week (5)

Order of Workouts

Studies show that performing strength training before endurance in concurrent training appears to be beneficial for lower body strength adaptations, while the improvement of aerobic capacity is not affected by training order (6)

Therefore, if strength is your priority, strength train first. If running is your priority, run first. If you’re training simply for health or for fun, do whichever fits best in your schedule first!

Duration & Intensity of Running

The majority of my reader audience identify as ultrarunners, and probably aren’t going to love this recommendation, but here we go:

If you are prioritizing any sort of hypertrophy, strength, or power gains…you’re probably going to want to avoid ultra-long distance running.

As mentioned early in this post, extended aerobic exercise does increase the percentage of contribution of energy coming from your muscle protein.

A recent meta-analysis reports that current evidence suggests that the interference effect of concurrent training on muscular strength or hypertrophy may be more pronounced by running compared with cycling, at least for type I fibers (4).

Further, there are studies suggesting that high intensity interval training may be a stimulus for inducing anabolic responses in skeletal muscle after concurrent exercise, compared to low or moderate-intensity continuous training (1)

So if you’re looking to make weight room gains, keep the cardio shorter.

So…Does Running Kill Your Strength Gains?

In short, the current evidence suggests that concurrent training may have a slight impact on your strength training gains, but likely not nearly to the extent that so many have come to fear.

Rather, there are so many other individual factors – such as nutritional status, sleep, rest/recovery, and training periodization – that may have an even greater impact on your strength training gains and your success in the weight room, than concurrent training.

Ultimately, both cardiovascular exercise – like running – and resistance training are necessary for optimal health. And chances are pretty good that the health benefits they bring together greatly outweigh any possible “negatives” when it comes to your sport or performance specific goal.

So, if you are a runner who loves strength training, or an avid weight lifter who occasionally enjoys running, take comfort in knowing that most likely, running is not going to totally destroy your gains.

Read more:

Strength Training for Trail & Ultra Runners: 11+ Pros, Cons, & Misconceptions

Simplifying Strength Training for Runners: 7 Moves to Balance Lifting & Running

8 Core Strengthening Exercises for Trail Runners (No Equipment Needed)

Resources:

- Fyfe, J. J., Bishop, D. J., Zacharewicz, E., Russell, A. P., & Stepto, N. K. (2016). Concurrent exercise incorporating high-intensity interval or continuous training modulates mTORC1 signaling and microRNA expression in human skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 310(11), R1297–R1311. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00479.2015

- Haff, G.G., & Triplett, T.N (2016). Essentials of Strength and Conditioning (4th ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Joanisse, S., McKendry, J., Lim, C., Nunes, E. A., Stokes, T., Mcleod, J. C., & Phillips, S. M. (2021). Understanding the effects of nutrition and post-exercise nutrition on skeletal muscle protein turnover: Insights from stable isotope studies. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 36, 56–77. doi:10.1016/j.nutos.2021.01.005

- Lundberg, T.R., Feuerbacher, J.F., Sünkeler, M. et al. The Effects of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training on Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01688-x

- Methenitis S. (2018). A Brief Review on Concurrent Training: From Laboratory to the Field. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 6(4), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports6040127

- Murlasits, Z., Kneffel, Z., & Thalib, L. (2018). The physiological effects of concurrent strength and endurance training sequence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of sports sciences, 36(11), 1212–1219. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1364405

- Robineau, J., Babault, N., Piscione, J., Lacome, M., & Bigard, A. X. (2016). Specific Training Effects of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Exercises Depend on Recovery Duration. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 30(3), 672–683. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000798

- Schumann, M., Feuerbacher, J. F., Sünkeler, M., Freitag, N., Rønnestad, B. R., Doma, K., & Lundberg, T. R. (2022). Compatibility of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training for Skeletal Muscle Size and Function: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 52(3), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01587-7

- Wilson, Jacob M.1; Marin, Pedro J.2,3; Rhea, Matthew R.4; Wilson, Stephanie M.C.1; Loenneke, Jeremy P.5; Anderson, Jody C.1 Concurrent Training, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: August 2012 – Volume 26 – Issue 8 – p 2293-2307 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d

Heather Hart is an ACSM certified Exercise Physiologist, NSCA Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), UESCA certified Ultrarunning Coach, RRCA certified Running Coach, co-founder of Hart Strength and Endurance Coaching, and creator of this site, Relentless Forward Commotion. She is a mom of two teen boys, and has been running and racing distances of 5K to 100+ miles for over a decade. Heather has been writing and encouraging others to find a love for fitness and movement since 2009.

Leave a Reply