Last Updated on April 14, 2018 by Heather Hart, ACSM EP, CSCS

Let’s get right to the painful, itchy topic: trail running and poison ivy. I imagined I’d be writing this post much later in the season. I did not imagine I’d be ignoring the dull roar of itchy skin while doing so. Alas, it’s early April and I’m already covered in a rash from a run in with poison ivy.

Ugh.

I grew up in the mountains of Vermont, during the era when moms would force you out the front door shortly after breakfast during summer vacation and tell you that you weren’t allowed back in the house unless someone lost a limb, or the sun went down, whichever came first. In today’s society, this might be considered child abuse. To me, it was the greatest gift my parents could have ever given me. As such, I spent much of my free time roaming around the woods, playing in overgrown fields, and exploring ponds, streams, and old barns. I remember countless scenarios when a soccer ball would wind up in a patch of poison ivy, and everyone would panic. “Don’t worry you guys, I’ll get it. I’m not allergic to poison ivy!” I’d shout with glee, as I’d frolic into the sea of shiny green plants, completely immune to their wrath.

Fast forward a few decades. I’ve discovered a love of trail running, and moved 1,000 miles South to a land where the plants are very, very angry. I’ve also discovered, the hard way, that I can no longer frolic through the fields of poison ivy, and emerge unscathed. Having been fortunate enough to have missed out on this misery for the first 32 years of my life, I realized I was pretty oblivious to how poison ivy, and the subsequent rash, even happen in the first place. And as someone who regularly frolics through the forest and the woods for fun, I figured it was time to learn a little bit about trail running and poison ivy.

Let’s start with the basics…

What causes a poison ivy (oak, sumac, etc.) reaction in the first place?

Poison ivy, as well as it’s cousins poison oak, and poison sumac, contain an oil called urushiol .

(For the sake of this blog post, I’m going to mostly refer solely to poison ivy, though the topics cover all three plants)

When the urushiol comes into contact with human skin, there is a delayed (sometimes a few hours, sometimes a few days) immune system response known as “delayed hypersensitivity”.

Here’s what happens, in a condensed easy to understand version:

When the urushiol penetrates the skin, the body’s immune system recognizes the urushiol as a foreign substance, and sends out it’s army to go to work. Among that army are the white blood cells, which are sent to the contact zone and turn into macrophages, then gobbling up the invaders. In doing so, however, normal, healthy tissues are damaged in the process, and the result is the itchy, oozy, sometimes painful rash. A common misconception is that the rash is a direct result of the plant touching the skin, when in fact, the rash is actually caused by our OWN immune system destroying cells in an attempt to rid itself of the foreign antigen.

(I’ll spare you the pictures of the poison ivy rash in this post.)

Can people really be “immune” to poison ivy?

Yes. No. Maybe. The answer seems pretty ambiguous. Most statistics will site the fact that 15% of our population does not experience a reaction to urushiol exposure. The bottom line seems to be that everyone has a different threshold of sensitivity to urushiol exposure. Some people will see a reaction with a very minimal exposure, some people need to practically roll around in a field of poison ivy for a reaction to occur. And further, just because you’ve never had a reaction to poison ivy in the past doesn’t mean you won’t in the future.

Sensitivity to poison ivy changes over time.

Many people who have never had a reaction to urushiol may develop a sensitivity after repeated exposure. Some internet anecdotes describe people who were incredibly sensitive to poison ivy for most of their lives, but suddenly never experience an allergic reaction again. In short, there seems to be no rhyme or reason as to when people become more – or less – allergic to poison ivy. So your best bet is simply steering clear.

Itching does NOT spread the rash.

We’ve established that the reaction time to urushiol can be delayed, depending on how much of the oil you have been exposed to. Further, the reaction time will be delayed depending on WHERE the exposure occurred. Sensitive, thin skin areas tend to develop a reaction sooner than thicker skinned parts of the body, as it takes longer for the urushiol to penetrate those areas. Therefore, it can appear the rash is “spreading” when really, the reaction time to exposure is simply delayed.

Further the oozy, bubbly parts of the rash? That is NOT urushiol from the poison ivy. That weepy fluid is actually created by your body, as an inflammatory reaction from exposure to the urushiol. It is not contagious, and will not spread the rash.

So in short, itching will not spread the poison ivy rash. However, itching can delay the healing process, create scarring, and introduce bacteria to an open wound, which is never a good idea. So it’s always best to avoid itching.

But the oil from poison ivy can linger.

All of that said, the oil itself CAN linger and remain potent long after it has left the plant itself. Oils lingering on clothing, tools, even a picnic bench or log you might sit on, can cause an allergic reaction. So if you know you have been exposed to urushiol from poison ivy/oak/sumac, be sure to wash anything else that might have also come in contact with the oil.

Trail Running and Poison Ivy: Preventative Measures

We’ve established what causes the awful rash associated with poison ivy (oak, sumac) contact. And we all know that trail running often takes place among the trees, shrubs, and…you guessed it…poison ivy plants. So how do you avoid succumbing to the horrible poison ivy itch while running?

Stay on the trails.

Avoid the urge to “bushwhack” or stray off of the trail. Not only will staying ON the beaten path help you avoid potentially running through poison ivy, but it’s also proper trail etiquette and helps to preserve the integrity of the trail and surrounding environment.

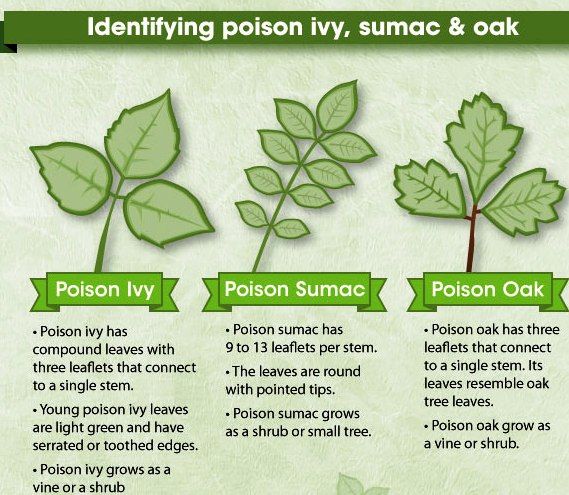

Learn to identify poison ivy.

If you can easily identify the plants you want to avoid, it’s significantly easier to prevent falling victim to the horrible poison ivy rash. The downside is that there are a bunch of plants that look very similar to poison ivy/oak/sumac and it can be hard to distinguish one from another. My advice? If you are highly susceptible to a urushiol reaction: don’t roll around (frolic, hold, etc.) in the plants, period.

photo credit: Angie’s List

Wear pants or tall socks.

If you know that running through tall brush is inevitable, consider your apparel. Wearing some sort of protective layer over your lower body (where you are most likely to come into contact with the oils of the plants) will help prevent direct skin exposure to the urushiol. Remember to immediately wash any clothing or gear that might have come in contact with the poison ivy plants, as the urushiol can linger on these surfaces and may inadvertently come in contact with your skin later. Keep in mind that many of these plants urushiol containing plants grow on vines, so they aren’t simply limited to ground height. Which brings us to our next point:

Be aware of what you lean or sit on.

As mentioned earlier, the urushiol of the poison ivy plant can linger on other objects. Further, poison ivy and poison oak vines can and will climb other trees and structures. Be aware of what you are leaning against, sitting on, leaping over, leaning gear against…you get the idea.

Shower immediately

If you can, shower immediately after leaving the trail to try and remove any urushiol on your skin. The sooner the better: according to the USDA, soap and water truly only works to remove urushiol if used within 10 minutes of exposure (source). Much of the internet seems to suggest liquid dish soap as the urushiol remover of choice, as it is relatively inexpensive, and designed to break up oils.

An alternative recommended by outdoor enthusiasts and professionals alike is to use specially designed urushiol remover, such as Tecnu poison ivy and poison oak scrub. (Amazon affiliate link) Tecnu can be used with or without water, making it easier to use right at the trailhead, if you know you’ve been exposed to poison ivy.

If you’ve spent your life being blissfully unaware of poison ivy (as I have), hopefully this post and these tips prove useful. When in doubt, remember the old saying:

“Leaves of three: let it be”. (except for poison sumac, which has 9-13 leaves. Nature is complicated.)

Here’s to another season of itch-free spring and summer trail running!

Heather Hart is an ACSM certified Exercise Physiologist, NSCA Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), UESCA certified Ultrarunning Coach, RRCA certified Running Coach, co-founder of Hart Strength and Endurance Coaching, and creator of this site, Relentless Forward Commotion. She is a mom of two teen boys, and has been running and racing distances of 5K to 100+ miles for over a decade. Heather has been writing and encouraging others to find a love for fitness and movement since 2009.

Carolyn

I am violently reactive to poison ivy and swear by Tecnu! It’s effective even after a rash has formed and will stop it, and the itchiness, in its tracks. I’m partial to the Tecnu scrub.

Madhu Basu

These tips are awesome. My town is extremely hot and humid, so wearing tall pants or socks is very uncomfortable. Can you suggest something else where I don’t have to wear tall pants and yet will be protected from these poisonous plants?

Annmarie Licatese

I also grew up where I explored the woods in Upstate NY but was/am allergic to poison ivy. My reaction hasn’t seemed to change at all and since I am going to be doing A LOT of trail running this summer, I am going to be utilizing these tips! Thank you!